Lake Malawi (Pic: Malawi24)

New Malawi water scheme is in the interest of a few, not the country

9 June 2017Malawi’s largest civil engineering company claims that the Lake Malawi Water Project is “immoral and fraudulent”.

by Tamanda Matebule

The boss of Malawi’s largest civil engineering company has attacked the roll-out of a $500-million scheme to supply Lilongwe with water from Lake Malawi as “immoral and fraudulent” and intended “systematically to siphon money for personal and political interests”.

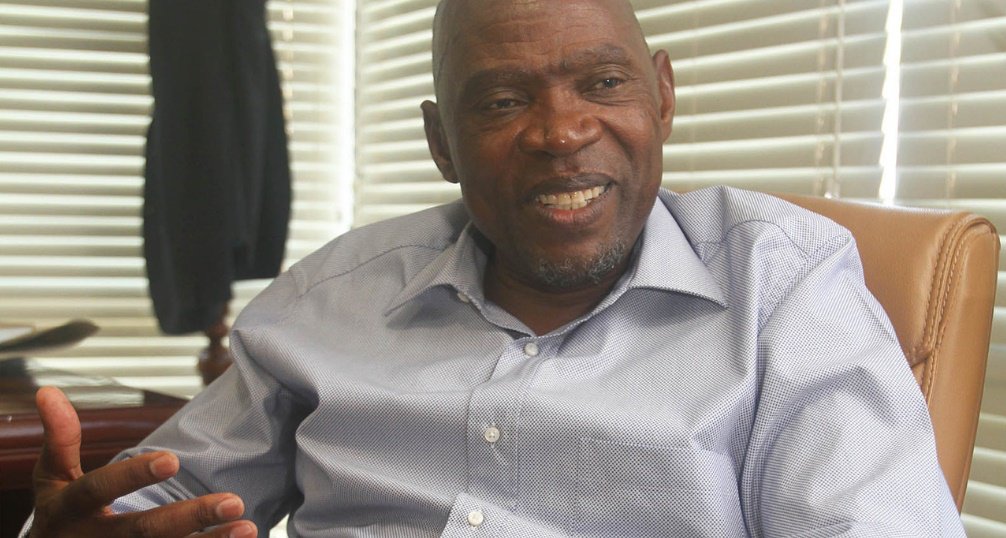

Newton Kambala, chief executive of Mkaka Construction, said that the Lake Malawi Water Project – also known as the Salima-Lilongwe Project – had been launched at the expense of the unfinished Diamphwi Dam scheme, which was far more viable.

Mkaka has done major projects in countries across the southern African region, including Angola, Mozambique and Zambia. It did not bid for either the Diamphwi or the Salima-Lilongwe contracts

“The Salima project is not in the national interest. Where on earth do you abandon a viable project for a fresh one? And where no environmental and social impact assessment has been conducted? Tell me, what’s this if not immorality of the highest order?” Kambala asked.

President Peter Mutharika’s spokesperson, Mgeme Kalilani, dismissed the allegation that the Salima contract would benefit only personal and political interests as “ridiculous and wild”. The contract “was awarded by Lilongwe Water Board [which] is not a political party,” Kalilani said.

The Diamphwi project would have gravity-fed water from a dam on the Diamphwi River in the hills above Lilongwe at an estimated cost of US$290-million, while the water from Lake Malawi will have to be pumped uphill through a head of 600m to the capital city 125km away.

Diamphwi was to be implemented by 2018 to enable the Lilongwe Water Board to meet growing demand for water in Lilongwe until 2040.

Work on it was suspended last year, and within months the Salima contract was awarded to Khato Civils, owned by controversial Malawian businessman Simbi Phiri.

Phiri recently told Malawi News that he has funded Mutharika’s governing Democratic Progressive Party, as well as the main opposition grouping, the Malawi Congress Party, and its leader, Lazarus Chakwera.

“You cannot do a project in an environment without knowing the technocrats, the politicians and the community, these are stakeholders … we have to engage,” he was quoted as saying.

Meanwhile, amaBhungane has established that Katho’s was the highest of six bids for the Salima contract, and that the second highest bid was US$200-million cheaper.

Sources close to the bidding process said that a Portuguese-based multinational, Mota Engil, put in a bid of $300-million.

“Where is the US$200 million difference going to?” Kambala asked. “I can promise you – the motivation behind this project isn’t to improve water service delivery. This is a jackpot for some individuals to rip off the poor nation.”

Kambala said Malawians should be worried about Phiri’s admission that he engaged with politicians. “Why must businesspeople directly support politicians, let alone political parties? Why must I go to State House to engage the president? What does this mean?”

Khato Civils spokesperson Taonga Botolo said he would “not be able to respond to the allegations that you make because they lack solid basis. Your allegations are mere insinuations that are made with malicious intent. “As a company, our eyes are set on mobilising resources in readiness for the water project, hence we have no time to waste on any elements desperately attempting to pull us down.”

Simbi Phiri (Pic: Malawi Independent)

Botolo did not respond directly to speculation that Phiri is shifting the focus of his business activities from South Africa to Malawi because he fears that President Jacob Zuma and his ministers may fall from power. Khato Civils has landed water contracts worth billions of rands in Giyani and Sweetwaters in South Africa under the watch of water minister Nomvula Mokonyane.

The water board’s chief executive, Alfonso Chikuni, said that the Diamphwi Dam scheme was suspended after the African Development Bank, rejected the board’s application for a loan. “We did not qualify for a loan in that category,” he said.

The other funder, the World Bank, had withdrawn its support after the government decided it was unable to carry the estimated US$25-million cost of resettling communities that would be displaced by the scheme. Asked whether communities might not also be displaced by the Salim project, he said this issue would be dealt with later.

“But for clarity’s sake, the Diamphwi river project has a lesser lifespan due to climatic variations,” he said.

On how the government could afford the Salima project, which was US$200-million more expensive, he said the two projects were independent of each other and should not be discussed in the same context. Subsequent attempts to contact Chikuni to ask why the board chose the highest bidder were unsuccessful.

The Lake Malawi scheme has also drawn fire from the Malawi parliament, academics, legal experts and environmental campaigners. The chairperson of the parliamentary committee on water development, Joseph Chidanti-Malunga, and MCP shadow minister Makuwa Mwale, both said there were many suspicions about the shifting of priorities and no convincing explanation from the water board.

“We’ve discovered that government lied to the nation,” Malunga said. “Initially we were told that government would only act as a guarantor if the Lilongwe Water Board defaulted on the Salima project. Now we learn that the finance ministry is trying to renegotiate the price.

“We find this odd and very suspicious. Why not use the loan for Salima-Lilongwe water project to complete the Diamphwi river project first?” queried Malunga.

Much of the concern hinges on the price of the work – thought to be the largest infrastructure contract ever awarded by the Malawi government – and the fact that it was handed out without a prior feasibility study and environmental and social impact assessments.

Critics have seized on the failure to assess the cost of electricity needed to pump water to Lilongwe. Malawi already struggles to meet electricity demand from households and industry and suffers from regular power blackouts.

According to the water board, the feasibility and impact studies are to be conducted by a Katho Civils subsidiary, South Zambezi. Critics have branded this a clear conflict of interests.

Kambala’s criticisms were echoed last week by the national coordinator of the Natural Resources Justice Network, Kossam Munthali, who said that “the natural resources sector questions the motivation behind the Salima-Lilongwe water project at the expense of a project [Diamphwi] where a commitment had already been made.

“We’re sceptical about whether this project is in the national interest, or is only meant to benefit a few”.

Munthali commented that statutory corporations such as the water board were not fully liable because they were prone to political and executive manipulation. “Board members operate at the mercy of the executive which is the appointment authority,” he said.

Mutharika’s spokesperson, Kalilani, said the President “has no influence whatsoever on matters such as awarding of business contracts the award of contracts”.

As the World Bank had pulled out of the Diamphwi scheme, anything connecting government to its suspension was “completely false“. “As a matter of fact the World Bank has now expressed interest to go back on the project, and they are talking to government about it,” he said.

The Salima project would benefit millions of Malawians from Salima and Dowa, where communities would be connected to the pipeline, and millions more in Lilongwe.

“The project has an estimated lifespan of one hundred years. Are you saying such a large-scale national investment is not of national interest?” Kalilani did not respond to a question about whether the Salima contract was unlawful because environmental law stipulates the need for a prior environmental impact assessment.

In another development, Malawi’s Anti-Corruption Bureau has revealed that it “has recorded a complaint … on the award of a contract to pump water from Lake Malawi to Lilongwe [and that] the Bureau will review the complaint to determine whether there is merit to warrant investigation”.

The bureau’s public relations manager, Egritta Ndala, would not comment further.

The World Bank did not respond to amaBhungane’s questions.

The amaBhungane Centre for Investigative Journalism produced this story. Like it? Be an amaB supporter and help us do more. Know more? Send us a tip-off.

Join the Conversation