Panama papers and the Choppies connection

25 April 2016A network of proxies assisted Farouk Ismail, one of the wealthiest men in Botswana and his family to secretly set up a property company in the tropical heaven of the Bahamas, documents contained in the Panama Papers show. INK Centre for Investigative Journalism reporters Joel Konopo and Ntibinyane Ntibinyane report

In 2013, Ismail sold part of his stake in Choppies, a major retail chain store in Botswana in an off-market transaction to Standard Chartered Bank Mauritius earning him over US$60 million.

The unprecedented leak from a Panama-based law firm, Mossack Fonseca, shows how the wealthy and powerful use a series of agents and lawyers to park their wealth in tax heavens in a way ordinary citizens cannot. Ismail is the founder and director of Choppies.

At least 121 Batswana, as well as a listed company, have been caught up in the resulting scandal, causing Botswana’s top judge, Ian Kirby (who has invested in seven off shore companies in the British Virgin Islands) to protest that his investment was above board.

The leak shines a sharp light on how the business elite in Botswana may be circumventing loopholes in the Botswana tax legislation to “wiggle out of” their obligation to pay tax at home. The documents do not establish that the Choppies magnate used the network of companies set up by Mossack Fonseca to evade taxes. The commercial purpose these companies served has yet to be plainly explained.

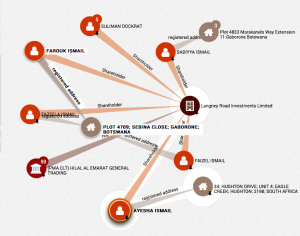

Documents obtained by a German newspaper, Suddeutsche Zeitung and shared by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), and to which INK Centre for Investigative Journalism has access, shows that in October 2014, Ismail and five members of his family used agents in London and Dubai to invest in Langney Road Investment Limited using an elaborate system, suggesting concealment, in the controversial tax haven of the Bahamas. Mossack Fonseca, a discredited law firm that has assisted politicians, criminals and gangsters to evade tax and hide funds offshore was subsequently used by Ismail’s agents to register the company in Bahamas.

Ismail who is the second largest shareholder in Choppies, listed on the Botswana Stock Exchange and Johannesburg Stock Exchange, has a shareholding of 14.6 percent valued at over US$100 million. The Ismail family seems to have used hidden behind a complex network of agents, using them to invest in London an undisclosed amount of money using a company registered in the Bahamas.

Ismail’s son, Faizel, and wife Fazeela as well as daughters, Sadiyya and Ayesha joined Langney, an “international business company,” four months after it was established by a Dubai – based front, Suliman Dockrat in October 2013, according to the Panama documents.

A certificate of incumbency shows that Langney’s “authorised capital” stood at US$50 000 in October 2013, which, according to the incumbency certificate is “divided into 50 000 shares with a par value of US$1 each.” Ismail and Faizel, hold a majority share of two shares each, while the four others have one. Docrat, who initially registered the company, subsequently resigned in February 10, 2014, the same day the Ismails took over the company.

Ismail’s investment in the tax haven coincided with his decision to sell off 12.7 percent of his Choppies shares to Standard Chartered Bank of Mauritius. He then opened an account with Standard Chartered Bank of London and transferred an undisclosed amount to the British Bank.

“When you sell shares, it is not taxable,” Ismail disclosed this week.

He invested in five “small” properties in London and says has not declared any dividends.

“If I declare dividends, I will pay Botswana Unified Revenue Services. I am still growing the portfolio.”

It is not clear why the family opened an account in the UK and bought a shelf company registered in the Bahamas that subsequently invested in shares in the UK.

Ismail also declined not disclose the amount invested in Langney.

Ismail avoided the question saying disclosure may open his family to become a target by criminals.

“The problem is of late there has been kidnappings, I could set myself to be a target of these sort of things.”

“These are small properties, its not anything big, “ he said, adding, “whatever rent we are collecting, we are paying tax in the UK.”

At a time when the Standard Chartered Bank transaction was being handled, Ismail and his son were also eyeing a franchise at Chicken Licken in Botswana. Newspaper reports at the time indicated that Faizel purchased a franchise of nine Chicken Licken stores in Botswana. Documents obtained from Registrar of Companies identify Faizel as the sole shareholder of Setso Home, a company that owns Ismail’s franchise.

More than 11 million documents were leaked Mossack Fonseca, revealing how it set up offshore companies for clients which could be used for tax avoidance purposes as well as alleged fraud and money laundering in some cases.

Fonseca says it complies with international protocols to ensure its companies are not used for money laundering, tax dodging or other illicit purposes, according to The Guardian. Yet the Panama papers have shone a light on a hidden world the firm says it does not recognize – one that sometimes facilitates crime, launders dirty money and finds ways of busting sanctions and evading tax.

How Ismail set up the offshore company

For the Choppies businessman, the offshore trail of companies and agents does, at face value, suggest a striving for secrecy. While such secrecy would certainly make it difficult for notional kidnappers to know that Ismail is a worthy target, this secrecy would incidentally also put Ismail’s financial affairs beyond the grasp of even the most feared tax inspector in Botswana. The trail starts through an agent in Dubai, then London, before darting to Mossack Fonseca in the Bahamas.

First, Leisure Homes, a property development company in Dubai took the trouble of registering a shelf company for a fee.

On 7 October 2013, Leisure Home’s, Nisha Krishna, coughed an orders to Mossack Fonseca (Bahamas): “Kindly request to check the availability of the following names for the purpose of opening new offshore company…. Do the needful.”

When Ismail wanted to open a bank account in Britain, another London – based property development firm, Urban Spectrum Property Management Limited stepped in. Four months later, Ismail and his son, Faizel would be included as Langney directors with two shares each.

While investing in a company in a tax haven may have an innocent explanation, none has so far been provided by Ismail. Asked to comment on the perception that his complex financial arrangements via Mossack Fonseca suggested that he had transactions to hide, Ismail replied: “I have no dealings what so ever in the Bahamas. My account is in the UK at Standard Chartered Bank. I am liable for global taxation.”

The Game of Taxation

Ranjith Ramachandran, Managing Director at Management Resource Centre, identifies working with “passive business investments” as part of his leisure. A chartered accountant and tax consultant, Ramachandran has worked for Choppies main shareholder, Ramachandran Ottapathu, for about two years as Chief Executive Officer at Liquorama, a liquor chain store. Ottapathu and his and former president, Festus Mogae have interests in Liquorama.

It is not clear whether or how Ramachandran is related to Ottapathu although they both originate from Kerala in India and have lived in Lobatse in Botswana. They denied any relation.

When asked to comment about Ismail’s businesses in tax heaven of Bahamas, Ottapathu said he was not aware of the investments and explained that Choppies directors are required to declare conflicting business interests.

“As long as there is no conflict, there is no obligation to declare personal investment,” he said.

The Panama papers also shine a particular light on the accountant, Ramachandran. Together with his colleague, Nndakumar Raja, Ramachandran was assisted by a South African law firm, Phatshoeane Henney Attorneys to secretly set up an offshore company, Exelle Financial International Limited in the British Virgin Islands in April 2008. The two worked for Mazars Accounting firm and sold their shares in the first week of December, 2009. Asked to explain the purpose of the tax haven investment, Ramachandran denied setting up a company in the British Virgin Islands.

“I got no idea on this shares and have not signed any documents relating to its acquisition or sale,” Ramachandran explained. He befriended Ottapathu in 1993 and later worked for him in 2008. “He is a friend of mine, we are from the same village in India,” he said about Ottapathu. His colleague, Raja was not available for comment

Join the Conversation