Botswana army patrolling Gaborone streets. Opposition say President Masisi passed emergency decrees and legislation expanding his reach during the pandemic

Coronavirus: Censorship is not the cure

25 April 2020Joel Konopo

The glitter of Botswana’s “shining example of democracy” is fading as the country of 2.3 million people slowly slides towards authoritarianism.

The trend began under former president Ian Khama, who silenced critical media and cowed citizens into apathy. His term in office ended in April 2018.

Early indications that his successor, Mokgweetsi Masisi – vice-president for four years – had a penchant for intolerance was evinced in the run-up to the ruling Botswana Democratic Party (BDP) congress in April 2019 when he openly thwarted his rival, Pelonomi Venson-Moitoi’s incipient challenge for the party presidency.

The Covid-19 pandemic has led to a further centralisation of power: Parliament recently passed an emergency bill that gives Masisi sweeping powers to rule by decree for a six-month period.

It was bulldozed through by the majority BDP in the teeth of opposition protests that putting power in the hands of one man will breed corruption and infringe on the powers of other branches of government.

As of Monday April 23, Botswana has reported one death and 22 cases of people infected with Covid-19. The country and has been placed under a 28-day lockdown, which ends on April 30.

Masisi and his government have not been able to explain the need for a lengthy state of emergency, except to argue vaguely that the Public Health Act is too weak to enforce a lockdown.

One alarming provision of the president’s emergency powers is the introduction of a prison term of up to five years or a $10 000 fine for anyone publishing information with “the intention to deceive” the public about Covid-19 or measures taken by government to address the disease.

Critics say the law, with broad and vague definitions, is a gift to authoritarian leaders who want to use the public health crisis to grab power and suppress freedom of speech.

Masisi’s backers argue that the law is needed as a deterrent. “It has become necessary to curtail some rights to prevent the spread of the virus,” said BDP spokesperson, Kagelelo Banks Kentse.

(See sidebar)

There are well-grounded fears that the emegency powers will be used to extend the government grip on supposedly independent institutions.

Already there are concerns that the security forces are meting out heavy-handed justice in the name of enforcing the lockdown.

Two police officers in central Botswana are facing assault charges, while a schoolteacher was arrested after challenging the government’s claim that a health worker who was screening lawmakers during a heated parliamentary debate on the state of emergency had tested positive for COVID-19.

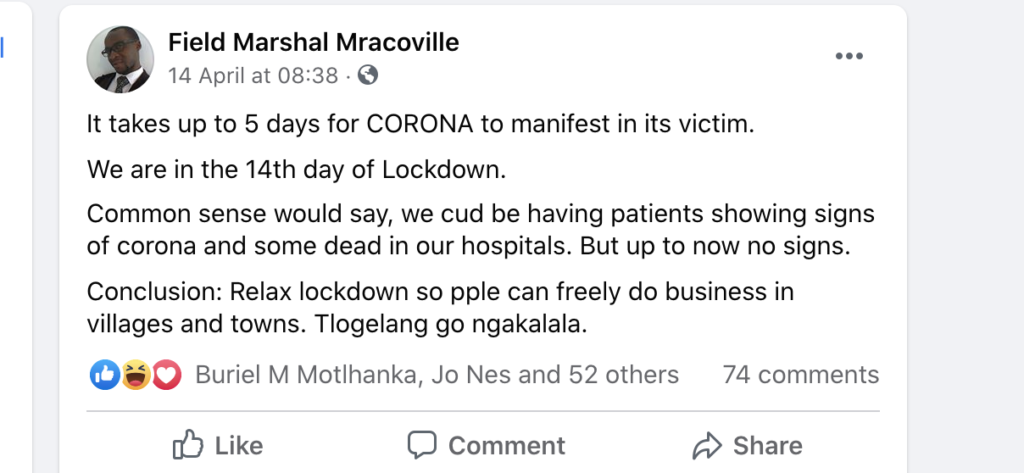

On his Facebook page , the teacher (who uses a pseudonym, Field Marshal Mracoville) also questioned why people infected with COVID-19 in hospital were not developing further complications or recovering.

“It takes five days for corona to manifest in its victim. We are in the 14th day of lockdown. Common sense says patients should be showing signs of infection,” said Rakkie Kelesamile.

Police say Kelesamile’s arrest is part of a larger effort to crack down on alleged “misinformation” under section 30 of the Emergency Powers Act.

His lawyer, Kgosietsile Ngakaagae complains that the government is trying to criminalise the airing of opinions.

“The interpretation of freedom of speech is wrong” he said. “Making personal observation should not be criminalised.”

Days earlier police had arrested Justice Motlhabane – the spokesperson of Botswana Patriotic Front, an opposition party with ties to former president Khama – for “degrading and maligning the leadership”.

The charges were labelled “worrying” by the Botswana Federation of Public, Private and Parastatal Sector Unions.

The charges were not brought under the Emergency Powers Act, but the country’s Penal Code. Under the Penal Code Motlhabane faces a potential fine of $50 or around P500.

Motlhabane and Oratile Dikologang are accused of suggesting on a Facebook page, Botswana Trending News, that Masisi had declared a lengthy state of emergency “so that he could deal with his political rivals and business competitors”.

A police spokesperson, assistant commissioner Dipheko Motube, said that the three men had published an “offensive statement against the government” as well as “degrading and maligning the leadership of the country”.

Motlhabane, who is out on bail, denied the charges, saying he does not have access to the Facebook account. He told INK Centre that the police gave him electrical shock treatment on several occasions, while demanding “certain information about a coup by the former president [Ian Khama].”

“They placed a Taser on my buttock and in between my thighs,” he claimed

His lawyer, Biggie Butale, and president of Botswana Patriotic Front said police do not have a case against his client.

“He is not the administrator of the Facebook account in question,” he said, adding: “Police never questioned him over Covid-19 – they asked him about a coup. You wonder what they are looking for.”

Several other people have been charged under the Emergency Powers Act.

A South African woman, Charmaine Ibrahim, appeared before court on March 27 for alleging that two fellow South Africans in Botswana have tested positive for COVID-19. Ibrahim, 35, is out on bail.

One lawyer, Mboki Chilisa, commented on social media that there is no point in punishing innocuous false statements “which no right-thinking member of the public could ever believe”.

The emergency powers also risk worsening already adversarial relationship between the government and private media.

The Act prohibits journalists from using “source(s) other than the [Botswana]Director of Health Services or the World Health Organisation” when reporting on Covid-19.

Journalists who use other sources potentially face a fine of $10 000 or a five-year jail term.

The executive director of the Media Institute of Southern Africa (Botswana Chapter), Tefo Phatshwane, objected that the emergency prohibits independent journalists from holding those in power to account.

He said Masisi has started a “censorship pandemic”, using wide-ranging restrictions as a cover to violate freedom of expression.

“As journalists, we can’t rely on a government that we are expected to police,” he says.

If coronavirus outbreak has taught us anything beyond the necessity of washing our hands, it is that its victim has been leadership.

Bureaucracy and incompetence have made it difficult to trust the WHO and governments world-wide.

On March 21, Masisi, who has a penchant for air travel, defied the lockdown to fly to Windhoek to witness the swearing in of Namibian president Hage Geingob.

He insisted that the trip was essential to enable leaders to discuss strategies to combat Covid-19.

Government also botched the handling of a death of Botswana’s first victim of Covid-19.

A local newspaper reported that the funeral of the elderly woman, from Ramotswa in the south-east of the country was not handled in a manner consistent with guidelines for the burial of victims.

Government admitted days later that she had died of the disease.

It is tempting to demand prompt action to combat those who undermine national and global efforts to combat the pandemic through disinformation. But Nkgakaagae insists censorship should not be part of the cure.

Government should identify the most efficient responses and communicate them to the public and allow reasonable and genuinely held opinions to flourish. “Government has to engage the public in dialogue,” he said.

Govt cracking down on Facebook hate-mongering – BDP

The following is a statement by Kagelelo Banks Kentse, a national executive committee member of the Botswana Democratic Party and the party’s spokesperson. Kentse was asked to comment on allegations that the government is using the Covid-19 crisis to repress journalists, critics and oppositionists, and to further centralise power.

It needs to be understood that the offences for which alleged perpetrators of Facebook hate-mongering are charged are transgressions against the Cyber Crime Act and the Penal Code. Thus, perpetrators would ordinarily be charged without the need for the declaration of a State of Public Emergency.

Their prosecution is unrelated to the State of Public Emergency and similar in fashion to a rapist who goes on rampage during the emergency. They may not be left unrestrained.

The need of a State of Public Emergency Government derives legitimacy from the Constitution and is bestowed custody of the Constitution on behalf of [Botswana’s] people.

The same Constitution has entrenched in its Bill of Rights personal liberties such as the right to religion, right of assembly and freedom of movement. In the fight against a pandemic like Covid-19 it becomes necessary to curtail some of these rights to prevent spread of the virus.

It therefore becomes imperative to invoke the necessary constitutional provisions to derogate the liberties enshrined in the Constitution. In Botswana, such provision is found under the State of Public Emergency powers bestowed on the President.

With the powers and regulations of the State of Emergency, and in the case of Covid-19, the President is able to suspend religious and social gatherings, suspend commercial activities and direct procurement of necessary equipment and services at a rate consonant with the fight against the pandemic.

It is necessary to point out that while the Director of Health is bestowed with powers under the Public Health Act, such powers are prescribed for when it may not be practicable for the President to invoke the powers of the Constitution.

The director’s powers are, therefore, temporary and subjugate to the authority of the President and the Constitution. They may, therefore, be applied temporarily in the planning or initial response period when the President gets briefing to develop a comprehensive response to a pandemic.

The director’s powers are also limited to specific areas within the country and may not be sufficient to combat the virulent spread of Covid-19 across the country, let alone control international travel.

Also, the Public Health Act is indisposed to commerce, and may not order a shutdown of commercial activity as is necessary in the fight against Covid-19.

Join the Conversation