Prisoners of Injustice

20 December 2017Over 500 rejected asylum seekers that arrived in Botswana looking for a better life more than two years ago have ended up in prison detention sharing facilities with convicted criminals.

Joel Konopo, Ntibinyane Ntibinyane, Olebile Letlole And Kaombona Kanani

Rejected asylum-seekers detained for long periods at the Francistown Centre for Illegal Immigrants (FCII) have accused prison officials of a pattern of ill-treatment including regular assaults and a failure to act on reports that boys as young as nine have been sexually abused.

Former FCII inmates also allege:

- that they and their children were confined alongside prisoners convicted of serious crimes, including murder and rape;

- that at least two asylum-seekers died after being denied adequate health care; and

- that army, police and intelligence operatives violently suppressed a protest by asylum-seekers, beating even children and a pregnant woman.

One consequence of the asylum-seekers’ lengthy internment is that close to 200 children of school-going age have not seen the inside of a classroom for two years.

The government has given a blanket denial of all the allegations, indicating that they are fabrications of desperate people.

The permanent secretary for justice, defence and security, Segakweng Tsiane, said the alleged abuse had not been mentioned to the officials who processed the asylum applications.

Many of the refugees have fled war and explosive ethnic rivalries in the Great Lakes region, where more than a million people have been displaced over the past two years, according to the International Red Cross.

The refugee influx into southern Africa has been particularly spurred by militia-based violence in Democratic Republic of Congo, particularly its easternmost province, Kivu.

Xenophobic attacks in South Africa have also swollen refugee numbers.

When scores of asylum-seekers crossed into Botswana in July 2015, their application for refugee status was swiftly refused, allegedly on the urging of senior officials in the Office of the President responsible for refugee policy.

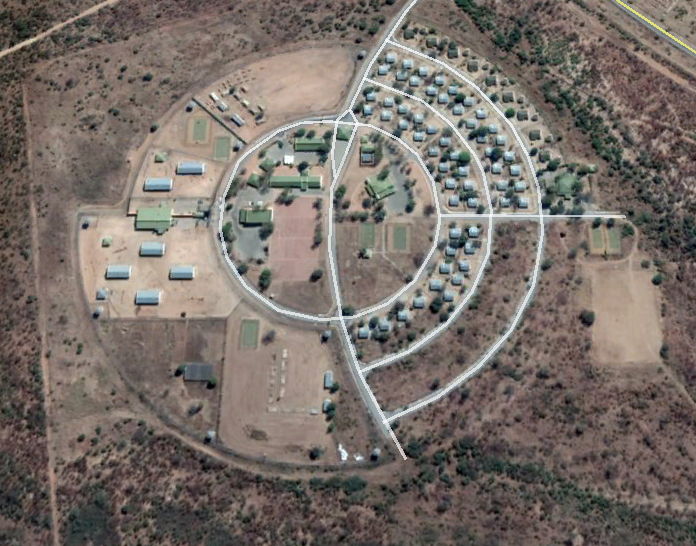

They were interned at the FCII in Francistown, northern Botswana, which began operating in 2002 as a holding facility for illegal immigrants but over time came to serve as a conventional prison for criminal offenders.

They now see themselves as being doubly victimised – by human rights abuses in their countries of origin and Botswana, which they chose as a refuge because of its good human rights record and reputation for respecting civil liberties.

The spotlight fell on the centre in July this year when 164 refugees petitioned the Francistown High Court to release them and order the government to facilitate their return to their countries of origin.

Complaining of “unbearable conditions” at the centre, they argued that they had been unlawfully detained beyond the 28 days permitted under refugee law.

The court upheld their plea, ordering the transfer of about 360 asylum-seekers and their family members to the Dukwi refugee camp, which offers educational facilities for children and allows some freedom of movement.

Four months later this was overturned on appeal. A panel of five judges led by Judge President Ian Kirby found that the failed asylum-seekers were illegal immigrants who were not protected by the Botswana’s constitution or entitled to the privileges of “recognised” refugees.

Kirby, a friend of President Ian Khama who is seen as a judicial conservative, ruled that a failure to uphold this distinction “could result in an uncontrollable influx of illegal immigrants from neighbouring and less stable countries”.

On the lower court’s assertion that it was international best practice to hold illegal immigrants separately from the general prison population, Kirby said this was not Botswana law.

He also found that legislation set no term for the detention of failed asylum-seekers, as repatriating them, involved “diplomatic exchanges that could take an extended period”.

However, the judge agreed that the FCII was a prison, which the government lawyers had denied.

In a four-month investigation of conditions in the FCII, the INK Centre for Investigative Journalism spoke to about 50 former detainees who are still living at the Dukwi camp.

They live in tents and use pit latrines, while the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the Botswana Red Cross and other charities provide them with food, shelter and medical care.

The government has not yet moved them back to the FCII, but they live in constant fear of being relocated.

For 16 year-old Selestin Ekima of South Kivu in the DRC, returning is not an option. “I would rather kill myself,” he said, a day after the Kirby judgment.

The ex-inmates alleged that they had all suffered degrading treatment at the hands of warders at the Francistown centre.

A satellite image of Francistown Centre for illegal Immigrants – a prison facility that houses both convicted criminals and rejected asylum seekers

They alleged that this included assaults, sometimes for the entertainment of the prison staff, but also in retaliation for complaints about the length of their detention and that they were not kept informed about how their cases were progressing.

The refugees told INK that on October 15 2015 the increasingly angry and despondent asylum-seekers staged a protest at the centre. “We wanted to know when we were getting out of prison,” one said.

They alleged that the prison authorities reacted by calling in the police, army and intelligence directorate to quell the demonstration.

“Women and children were severely beaten – even children as young as a year old and a heavily pregnant woman were not spared. It was a sorry sight – I had never seen anything like it,” said Benjamin Katumbi from the DRC.

The alleged instigators were sent to Francistown maximum security prison as a punishment. “I spent 10 days there, over and above the beatings I suffered at the hands of the security officers, I lost a front tooth in the beating,” said Abrizak Abdul, a Somali.

Manyempudu Bahati Ghadi (30) was also sent to the maximum prison as an alleged instigator. There, he says, convicted criminals repeatedly sodomised him over more than two months. He counts himself lucky that he did not contract HIV/Aids, as his attackers used no protection.

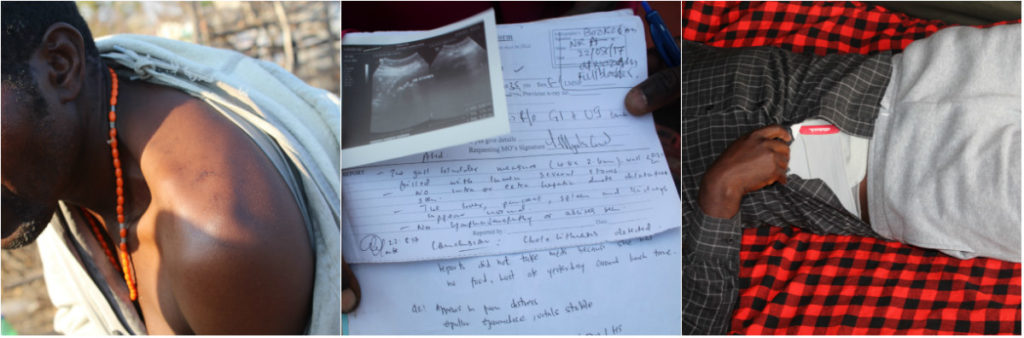

Ghadi said abuse at the FCII was a constant occurrence. “The first time I was assaulted in 2014, I suffered a serious neck injury that resulted in me having to wear a neck collar for five months,” he alleged.

As a result of constant beatings at FCII Ghadi is nursing “loss of lumbar lordosis” and “degenerative changes of the lumbar spine”

He said he had been tortured or beaten on three occasions since 2013, when he first arrived at the facility. Ghadi is nursing “loss of lumbar lordosis” and “degenerative changes of the lumbar spine”, according to his medical reports, which INK has seen. He walks with crutches.

Exode Kiza fled ethnic violence in his native Rwanda, escaping with his partner and eight-month baby after his family threatened to kill him for marrying a “Banyamulenge”, a Congolese Tutsi with Rwandese roots.

Kiza alleges that he was treated as a prisoner rather than a refugee at the FCII, and that the warders there subjected him to regular beatings and monthly searches.

Some inmates gave accounts of how convicted criminals at the FCII targeted boys, using food to lure them into sex. An 11-year-old boy, whose identity cannot be revealed, said a convicted criminal used food to lure him to his cell where he raped him.

“I shouted for help but no one came to my rescue,” he said. When he reported the incident to the prison warders he was told to go away.

This 11 year boy was sexually assaulted by one of the convicted criminals at FCII.

The prison had taken no action to protect the children, the former inmates alleged. The boy’s mother said she found her son’s experience particularly painful given the violence the family was subjected to in the DRC two years earlier.

She said her husband had been murdered in the presence of their two sons. “I was later gang-raped in front of them. And now I have to deal with the fact that my son was also raped in prison here in Botswana,” she said, in tears.

The ex-inmates alleged that convicts hired by the centre to prepare food for the asylum-seekers often used food to bribe young boys.

“Those who agreed to sleep with the convicts were often rewarded with more food, while those that refused got no food,” said James Katumbi, an asylum-seeker who has spent three years at the FCII.

‘Neglect led to deaths’

Family members also claim that the death of two refugees was the result of medical neglect. Kashindi Bawili a 33-year-old Burundian national and hypertension patient, collapsed and died on December 8 2015 a few months after arriving at the detention Centre.

Members of his family, who were also his cellmates, said that before his death he complained that he was not receiving medication for his condition.

“Minutes after he collapsed, I asked the prison warders to be allowed to accompany him to the hospital, but the request was denied,” said his uncle, Tambwe Mbuku Simon.

“We only learned [of his death] few days later when we were issued with his death certificate.” The certificate gives the cause of death as “cerebrovascular accident or stroke”.

Bawili left two sons who were granted refuge by the government. “Immediately after the two kids were granted refuge they were taken away from us by the government,” said Simon. “To this day we don’t know where they are.”

Misspelled grave of Kashindi Bawili. He died at FCII allegedly because he was neglected by prison officers. He was a hypertension patient

Kiji Molondela, 30-year-old asylum seeker from DRC, died in September 2016 when he did not receive adequate treatment for a liver condition, according to his relative, Steve Manu.

Molondela’s former cellmates said that he arrived in Botswana in 2015 after fleeing xenophobic violence in South Africa. They allege that despite his pleas to the prison officials that his condition needed urgent attention, nothing was done to assist him.

“He was only taken to the doctor when it was too late. The prison officials just didn’t care,” said Manu.

INK was told that several cases of abuse have been reported to the Botswana authorities and to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in Gaborone.

In response to inquiries, the UNHCR did not address specific issues raised by the refugees, but instead commented that “the detention [in prison] of the asylum seekers and refugees has a serious and lasting effect on individuals and families”. (See UNHCR response)

A well-placed government source also said tensions between the UNHCR and the government have adversely affected the interests of asylum-seekers. In particular, the government is said to have been angered by a UNHCR decision to relocate its regional office to Pretoria in South Africa.

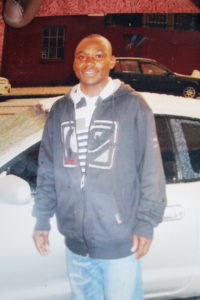

Molondela died in 2016 allegedly because he did not receive adequate treatment for a liver condition

With fewer than 3 000 refugees, both Botswana and Namibia fall below the UNHCR threshold for a permanent office.

A senior regional protection officer is said to have been denied permission to enter FCII, heightening tensions. It is understood that the UNHCR has now abandoned plans to relocate the refugees.

‘It’s all lies’

At a press conference, permanent secretary for justice, defence and security Tsiane, denied that the asylum-seekers were being kept in a prison and that they were constantly subjected to abuse.

“What I can say is that it is not true. Yes, they share the same campus [as ordinary convicts] but the structures are divided. Convicted prisoners are confined to the cells but asylum-seekers are not,” said Tsiane.

However, she conceded that convicts are used to prepare and serve food to the refugees, but insisted that the two groups do not eat in the same area.

Tsiane confirmed that family members, including children, are separated from each other at the centre, but said this is a precaution to prevent men and women sharing facilities.

She described the allegations of abuse by asylum-seekers as “fabrications” that were not consistent with what they told government officials who reviewed their asylum applications.

“Some of them told us that they sustained some of the wounds in their home countries. But we are not surprised that they are now turning around to allege that they were beaten by prison officials here. It’s all lies, blue lies,” she said.

“If there is evidence that our people abused the rejected asylum-seekers, we will investigate and take appropriate action. We don’t condone abuse, the prison regulations are clear.”

Tsiane added that the prison authorities had never called in members of the police, defence force or intelligence directorate to assault asylum-seekers who were protesting against their conditions. “That has never happened; it’s a lie,” she said.

She said the government is working with the authorities in the DRC government to repatriate the remaining 134 refugees who applications for asylum were rejected.

https://www.dropbox.com/s/yiichto3mhcr0wt/Prisoners%20of%20Injustice.pdf?dl=0

Join the Conversation