EXCLUSIVE: Khama’s Mosu built with public funds

18 June 2017by INK Reporters

Botswana Defence Force (BDF) funds, equipment and personnel are being diverted towards constructing and developing President Ian Khama’s private lodge at Mosu, on the southern shore of Makgadikgadi Salt Pans, a prime tourism destination.

Investigations by INK and Sunday Standard have also revealed that Khama, who is one of the biggest tourism investors in Botswana, appropriated a chunk of land to add to the 60ha in Mosu which he has been allocated by the Letlhakane sub-land board for a commercial tourism business.

Satellite images have revealed for the first time how government has for years maintained a veil of secrecy over the huge construction work going on at the president’s property in Mosu, consistently downplaying the size, scale, and scope of the controversial project. INK and Sunday Standard contracted DigitalGlobe, a New York-listed commercial imagery firm, to capture a high-resolution 50cm worldview image over Mosu private property and airstrip. DigitalGlobe sub-contracted Johannesburg-based Swift Geospatial Solutions.

In July 2014, the Office of the President claimed that: “The President’s house is a single bedroom cottage with a kitchen and a sitting room, while his brothers between them have a two-bedroom cottage and a single-room chalet.

“There is also an additional single room chalet at the compound. During all phases of the construction undertaken at the compound, that is on the homes of H.E. the President, his brothers and the guest chalet, no Government personnel were engaged. Neither was any government money spent on the structures.” The satellite impressions commissioned by INK and Sunday Standard contradict the official narrative that BDF resources have not been deployed in Mosu for the President’s personal gain.

Imaging satellites operated by Swift Geospatial Solutions exposed the President’s property as a huge military installation which is much larger than previously stated by the Office of the President. One of the plots is 15 hectares of military equipment: Earth moving machinery, water bowsers, large trucks, smaller utility trucks, a solar panel plant, a large generator and and three rectangular structures – which according to an architect contracted by INK resemble army barracks.

Satellite images show that major developments are taking place at President Khama’s holiday home at Mosu [DigitalGlobe]

A fireplace (kgotla) enjoys the pride of place among military hardware at the centre of the compound. Completing the picture of a luxury eco-retreat outback is 79 square metre helipad and a tower jutting out of a sprawling housing complex of 22 buildings linked to a 45 hectares airstrip with a 1.6 kilometres runway – long enough to accommodate even the Directorate of Intelligence and Security Services (DISS) Pilatus PC-24 twin engine business jet.

The two properties are separated only by a 200m road climbing over a culvert that bridges them into a commercial conurbation turning the Mosu complex into the ultimate experience in glamping, for tourists seeking the luxuries of hotel accommodation alongside the escapism and adventure reaction of camping. Two unsheltered aeroplane bays seal each end of the runway which sticks out like a red scar against a dark grey background.

Investigations reveal that the developments at Mosu are designed to enhance the compound’s capacity to host VIP guests and their retinues upon Khama’s “retirement”.

Government statements on the President’s residence have tried to divorce his residential plot from the airstrip. The official spin sought to exonerate the President from any private benefit arising from the BDF involvement in Mosu by implying that the airstrip is neither his personal use nor in his property. The Mosu residence-cum-lodge, which is nestled in the south of Sua Pan, in the eastern half of Makgadikgadi Pan, is a major migratory path for bird life and a gateway to the already rich eco-tourism destination.

While major construction sites are required by law to post signboards cataloguing the civil engineers, construction companies and quality surveys carrying out the works, there is no signage at Mosu to indicate that major construction work is in progress.

The developments captured on the INK and Sunday Standardsatellite images, however, reveal that substantial construction work has been going on since the area was captured on Google Earth in 2012 when it only had a helipad and a small cluster of chalets for Khama’s two brothers, Tshekedi and Anthony, and their sister, Jacqueline.

Google Earth provides free online satellite images of the world. The images obtained by INK and Sunday Standard, unlike the archived images by Google Earth are in real time.

A soldier engaged on the development has revealed that following media revelations of BDF deployment at Mosu in 2013, heavy construction only resumed in earnest last year October (2016) for the final phase of extensions and developments to the property in preparation for Khama’s retirement in nine months.

The source told INK that equipment on site includes two BDF-registered earth-movers, a cement-mixer, a grader and “more than 60 BDF construction workers”.

President Khama’s Mosu compound in 2010

Another security force source revealed that the use of BDF personnel for Khama’s private interests was not a new development. He added that members of the BDF have “always” been deployed for Khama’s personal benefit.

The source explained that the developments at Mosu intensified in October 2016 after the outgoing BDF commander, Lieutenant General Gaolathe Galebotswe, withdrew BDF construction equipment at the residence in preparation for the handover of the BDF to its current commander, Lieutenant General Placid Segokgo.

An additional source claims that Galebotswe withdrew the BDF equipment and personnel in retaliation against Khama’s refusal to renew his contract. Galebotswe denies the allegations and insists that his relationship with Khama remains cordial.

The security force source in addition revealed that the removal of BDF personnel and equipment infuriated Khama who ordered its immediate return and for construction to resume.

Government spokesperson Jeff Ramsay, however, denied reports that developments at Mosu are for the President’s personal use. The explanation offered by Ramsay does not address the beneficial gain that will accrue to the registered owner of the airstrip – Khama.

Ramsay informed INK that “the only significant recent activity (at the residence) involved renovation of the helipad, which was suspended due to rains but (the construction) will continue”.

BDF refused to comment, other than to say they share Ramsay’s views on the developments. The satellite images, however, show no sign that the 79 square metre helipad is currently under construction.

A completed helipad inscribed with a letter “H” can be seen at the south-eastern end of the compound. Google Earth satellite images captured in 2012 reveal no differentiation in the images of the helipad, suggesting that the helipad has not undergone any major construction over the last five years.

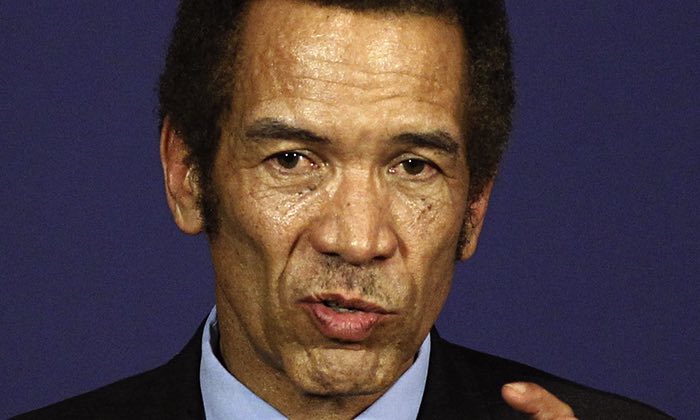

President Khama [Pic theguardian.com]

Media reports have indicated that Khama moved into Mosu in the late 2000s after the Letlhakane sub-land board allocated him two plots totalling 1.1 square kilometres for the construction of a lodge and compound.

Additional media reports indicates that Khama’s former private secretary, Isaac Kgosi (now the Director of DISS), represented his boss during meetings for the allocation of the two plots and water connection by the Department of Water Affairs.

Kgosi has refused to discuss the matter, saying he would not engage with the media on the President’s personal affairs.

The development of Mosu was estimated in 2013 to cost P3-million. While the costs may have escalated due to construction delays, as alluded to by Ramsay, INK as a result has not been able to establish either the time-frame for the project’s completion or ultimate cost, given the secrecy surrounding the project.

Contrary to the government’s statement in 2013 that the airstrip was merely going to be gravelled, the images reveal extensive engineering works complete with a well-structured drainage, using a system of culverts and raised ground level for the untarred runway.

Sources reveal that the airstrip has been designed and built and not merely graded. Expanded satellite images show a stone quarry that provided gravel for the works.

The controversy surrounding the ownership of the airstrip, whether for private or public use has arisen due to the persistent inconsistent explanations by government. Ramsay told Botswana Guardian in 2013 that “original request to the Letlhakane sub-land board for the airstrip was in the name of the President rather than his office”.

[The] original request to the Letlhakane sub-land board for the airstrip was in the name of the President rather than his office”.

Following INK’s investigations, Ramsay shifted from his earlier position. He explained that the airstrip is a “strategic” facility registered with the Civil Aviation Authority of Botswana (CAAB) that will “continue to be managed by the BDF as part of its strategic support of the President” and be handed to the authority when Khama leaves office.

The explanation by government fails to unravel why a “strategic airstrip”, which is intended to cater for national emergencies, was applied for in the President’s personal name and not the name of the appropriate ministry.

It is not clear how Civil Aviation Authority Botswana (CAAB) will manage the private airstrip, which will from April 2018 belong to a former president and private citizen enjoying the legal rights accruing to the property to the exclusion of all others.

CAAB public affairs manager Modipe Nkwe, in response to questions by INK, was non-committal on the management of the airstrip, but echoed Ramsay’s view that it is one of 22 strategic airstrips in Botswana falling under the authority.

Following the arrest and detention of INK reporters who sought to view Khama’s compound at Mosu, Ramsay informed INK that it was a “restricted area (that) required official clearance to enter”.

He refused to be drawn into discussions on whether the President’s residence is protected under law. “I fail to see the relevance of Protected Places and Areas Act in this context, but perhaps others can assist you (to) better understand the restrictions in the context of presidential security,” he said.

He referred INK to Khama’s private secretary, Gobe Pitso who said government had been responding to media questions on Mosu over the past four years. “Nothing has changed,” he said.

The Protected Areas and Places Act, which provides “for the declaration of protected places and protected areas, to regulate the entry of persons into such places and areas” lists specific areas and properties that are published in the Government Gazette as protected areas. The Act makes no mention of Khama’s Mosu property. The Act does not extend to images obtained from satellite.

The government statement on the incident involving INK journalists, said the three journalists were attempting to trespass in a restricted area. The area is closely guarded – so much so that security agents on patrol restrict the movement of local peasant farmers.

Since you are here... We have a favour to ask you. To get involved and support good journalism by INK Centre for Investigative Journalism click links below To Get Involved To become a supporter

Join the Conversation