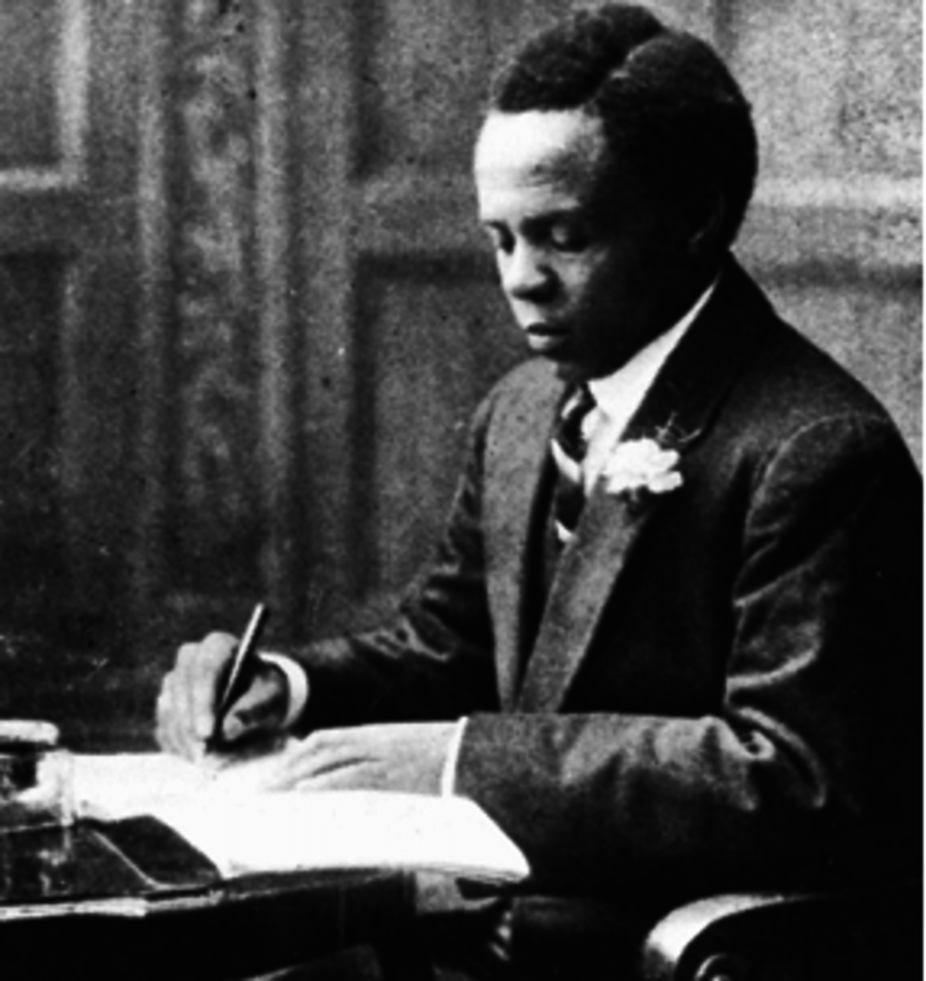

Sol Plaatje (Wits University)

World Press Freedom Day – A tribute to Africa’s Journalist

5 May 2017As the world commemorates World Press Freedom Day INK Centre for Investigative Journalism’s NTIBINYANE NTIBINYANE pauses to pay tribute to Sol Plaatje, one of the founders of independent journalism in Africa.

Sol Plaatje (Wits University)

World Press Freedom Day, 3rd of May is a day to commemorate the contribution of the media to democracy, justice and social reform. It is a day that recognises the contribution of not just the role of the media, but the contribution media activists make to drive social change and address the injustices that prevail in our society.

Born in the Orange Free State province on October 9, 1876 Solomon Thekisho Plaatje became more than a mere journalist, he was an icon of the struggle for African liberation and social reform. He will of course always receive tribute as one of the founding members of the African National Congress (ANC) but it was his career as a journalist that set him on the path of political activism.

At a time when freedom of expression and press are increasingly under threat by growing authoritarianism, INK pays homage to one of Africa’s finest sons, Solomon Tshekisho Plaatje, journalist, writer, poet, linguist and political activist, and looks for the rebirth of the spirit of journalism that Plaatje personified.

Before the advent of television, before the arrival of radio in Africa, before the Internet, before the birth of the cellular phone and certainly before Facebook “activism”, good journalism took pride of place. Operating under extreme censorship and confined by the limitations of its time, journalism in Africa produced men and women that used the power of the pen to tell African stories, challenge power and exposed heinous injustices that came with colonisation and racial discrimination.

At a time when the world is commemorating the World Press Freedom Day, one of the foremost names that comes to mind is that of Solomon Tshekisho Plaatje or Sol Plaatje as he was best known, for his contribution to African politics, literature, linguistics and mostly importantly, on the occasion of the world press freedom day, to journalism. As one of the pioneers of independent African journalism at the beginning of the 20th century, Plaatje’s contribution to journalism in South Africa and the British Protectorate of Bechuanaland is enormous.

Plaatje was not merely journalist, he was a complete journalist; a pioneer of pioneers. Plaatje was a journalist, an editor and a publisher all at the same time. He impacted on many in South Africa and Bechuanaland through his commentary on social injustices in his newspapers, Koranta ea Becuana and Tsla ea Becoana (later renamed Tsala ya batho).

It is important to acknowledge that before he established these two iconic newspapers, Plaatje was a court interpreter in Mafikeng due to his prodigious love of language and his ability to speak seven languages fluently. It was this love of language that drove him to keep a personal diary in which he recorded the events of the bitter Anglo Boer war. The diary is considered by many to be the birth of African literature.

Caught in the siege of Mafikeng, Plaatje became a pioneer war correspondent before many dared to venture into this perilous genre of journalism. It was during the siege of Mafikeng by the Boers that he wrote several articles for the Mafikeng Mail using a pseudo name. His hand-written diary about the seven-month ‘Siege of Mafikeng’ is the only African account of the attempt by the Boers to capture the town.

In spite of his personal achievements however, it would be remiss to talk about Plaatje’s early journalism work without mentioning Silas Molema, a leading member of Barolong Tshidi in Mafikeng. According to historians, it was probably Molema who interceded on Plaatje’s behalf to get him the interpreter’s job and more importantly to fund Plaatje’s first newspaper Koranta ea Becoana to the considerable tune of 25 pounds!

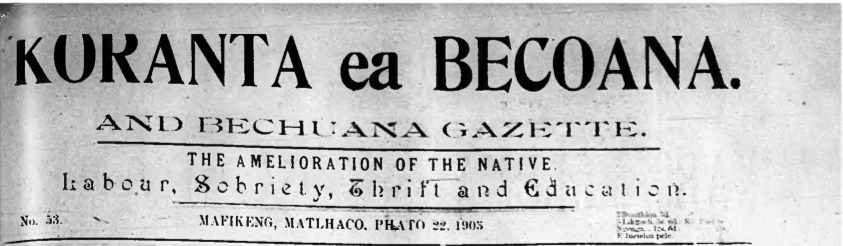

The 1905 masthead of Koranta ea Becoana (Wits University)

The story of how Koranta ea Becoana came about is a fascinating one. According to historian Brian Willian, in April 1901, the owner of Mafikeng Mail, GNH Whales introduced for the first time a one-paged supplement within Mafikeng Mail that was written in Tswana to maximize profits by reaching out to Africans in Mafikeng. The supplement was called Koranta ea Becoana or ‘Becoana Gazette’ as it was referred in English. Since Whales did not know how to read and write Tswana he roped in Plaatje and Molema to edit the supplement. After 12 issues that appeared at irregular intervals, Plaatje convinced Whales to sell him the supplement with the assistance of Molema who contributed £25 to create South Africa’s first black owned independent newspaper in September 1901. At the age of 25 Plaatje was not only the editor of a newspaper but also its founder and co-owner. He would later tell a 1904 government commission on native newspapers that, “I just started it as an enterprise, and one of the chiefs (Molema) financed.” According to another historian Les Switzer, with an initial circulation of about 500, the one page newspaper was increased to two pages, newsagents were appointed, and for the first time advertising was solicited. Perhaps the biggest boost to the paper was the decision by the resident commissioner of Bechuanaland Protectorate to advertise government notices in the paper.

One of the most overlooked achievements by Plaatje is that together with Molema, he was one of the first Africans to own and successfully run a printing press in 1902. The two later formed a company called Bechuana Printing Works. In August 2, 1902 the paper was launched amid pomp and fanfare. At the re-launch of the paper, the Mafikeng Magistrate and Civil commissioner Mr. Graham Green was invited to officially open the new printing plant. It is perhaps Mr. Green’s words at the official opening that demonstrated the importance of Koranta ea Becoana in Mafikeng and beyond, according to historian Willian. “The press, during the past three years have been greatly responsible for the varied feelings that have moved various classes of the people and I do trust that that the paper will be published in the interest of the truth, justice and charity. Of truth, that its news may be reliable and verified, before publication; of justice, that it will see that the weak are not oppressed and that the law is upheld; and of charity, that its personal criticism will be for the public benefit, and not to satisfy the personal feelings of the writer.”

“I do trust that that the paper will be published in the interest of the truth, justice and charity” – Graham Green in 1902 at the Launch of Koranta ea Becoana

It can be argued that as Green advised at the launch, Koranta ea Becoana upheld some of the principles of truth, justice and charity in its reportage and editorial columns. The newspaper carried content that challenged oppression of Africans by the white minority government. The paper was vocal on issues of equal rights, equality of opportunity, and equality before the law. In one of the newspaper’s fiercest editorials in 1903 (that this author reviewed), Plaatje called on the British government to have fair remuneration for Africans. Using his wide range of knowledge he combined an understanding of economics and politics to express the view that it wasn’t justified for Africans to be paid the meagre wages that they were receiving for their labour, “We are willing to work, but for nothing less than a living wage. One shilling a day maybe good pay in Europe and India where we are told that one can obtain a decent meal at a penny, but it is quite the reverse in this country where one cannot obtain a meal at anything less than one shilling. Pay and we shall belt up.” His use of the term “living wage” placed him well in ahead of the thinking of the times as the demand for a living wage continues to this day and set government policy in the post-Apartheid era.

In the context of Botswana and its independence, perhaps one of the paper’s most important political campaigns was its opposition to the proposed annexation of Mafikeng and the rest of Bechuanaland by the British to the British colony of Transvaal by influential British businessmen in Mafikeng. They had succeeded in getting the support of the local Barolong chiefs and were only waiting for the arrival of the British Secretary for Colonies Joseph Chamberlain to present the joint proposal to him. After it was leaked to the paper that the whites had schemed with the local chiefs for Mafikeng and Bechuanaland to be annexed into Transvaal, Koranta ea Becoana launched a spirited campaign against the proposed annexation. In one of its editorial the newspaper wrote a strong editorial, denouncing the petition, “This action on their [the chiefs] part is nothing but a terrible leap in the dark and never was there a mere flagrant case of wilful political suicide than there is in this movement; and we earnestly trust that for the sake of our ourselves the Chiefs will see to its early withdrawal before it is too late”.

Under pressure due to the exposé, Barolong chiefs withdrew their support of the annexation in a letter that appeared in Koranta ea Becoana a week after Plaatje’s scathing editorial. According to Willan when Chamberlain arrived in Mafikeng the British businessman presented him with the annexation proposal but Chamberlain refused to agree to it because it carried no African support, thus history tells it’s own tale, Mafikeng and the rest of Bechuanaland were saved from annexation. Through the power of the pen, Plaatje and his paper had won a significant battle that saved Bechuanaland (our present day Botswana from annexation). This also further demonstrated that as an editor and journalist Plaatje had an independent mind and he wasn’t afraid to criticise his own chiefs.

The paper’s advocacy journalism grew over the years. One notable story that newspaper covered was the conviction and wrongful sentencing to death of two Boers that had been accused of murder. Plaatje a former court interpreter with knowledge of the law condemned the sentencing and advised the court through his editorials that the men should not be put to death but given lengthy prison sentence. The Griqualand West High judge later realised the mistake and changed the sentence to jail term. According to Willian, predictably Africans condemned Plaatje for his campaign to spare lives of the Boers. However the counter argument was that as a man of principle Plaatje was not afraid to take an independent inline on causes of justice for all, even if it was likely to make him unpopular.

Despite its growing popularity and in fact due to its increasing popularity, the paper and its editor were not immune from criticism and abuse in particular from white press and government officials. In 1905 after criticising the white administrations of Transvaal and Orange Free State, one of the white owned Johannesburg papers accused Plaatje of sedition and wrote the following about Plaatje; “Disloyalty, now-a-days, is the refuge of the ignorant. It has sunk down to the level of a Kaffir past time. The editor of the Mafikeng Kaffir newspaper, Koranta ea Becoana, is a seditious person who used to interpret at the Magistrate’s Court. He got into the habit of thinking during the course of his duties, and a lot of stored up, compressed thought drove him into journalism as an outlet for it. Thinking, however is a bad thing to get into late in life, if you haven’t been used to it before. One is apt to get a wrong perspective and when he complains of British rule it is an evidence of it.” The criticism of Plaatje’s newspaper resonates equally today, less the blatant racial slurs, with authoritarian regimes.

In the face of abusive treatment from white press, Koranta persevered and expanded the protest agenda and campaigned for better treatment of Africans. The paper was a huge success that it was occasionally quoted in parliament. The paper and Plaatje grew in status and popularity.

After his involvement in the formation of the ANC, Plaatje was unable to obtain funding for his newspapers, which could not survive on the income from sales alone and like most other black protest newspapers Plaatje’s newspapers closed down after few years. Koranta ea Becoana closed down after seven years, Tsala ea Becoana closed down after two years and the more militant and loved Tsala ea Batho collapsed after three years.

Sol Plaatje (Seated far left) with founding members of the African National Congress

Of course Plaatje and other African journalism pioneers operated under a different political, economic and social order, but surely there are lessons to learn from this pioneer. While the agenda setting function of newspapers and legacy media in 2017 has shifted slightly to social media, and perhaps algorithms, newspapers and other traditional media has a lot to learn from Plaatje’s approach to journalism.

Sol Plaatje was an advocacy journalist; he had a clear agenda of what was needed to be done to improve the lives of Africans. Was he a partisan journalist? Indeed he was, the then prevailing conditions forced him to be a partisan journalist. Despite this he published his stories in the interest of truth, justice and social reform. History has vindicated him.

Do we have such journalists today? Are we publishing our work in the interest of truth, justice and social reform? Are we fearless in the way we convey messages to the citizenry? Do we effectively hold power to account? Do we cow in the face of criticism, harassment and intimidation?

As an editor Plaatje put good journalism first. His newspapers were not afraid to pursue the truth and take and defend unpopular viewpoints. When his newspapers struggled financially Sol Plaatje did not sell his soul to the government or business interests of that day. Instead he stood by principle, choosing rather to go bankrupt than to be captured by special interests.

His iconic words expressing his anger at the 1913 Natives’ Land Act ring true today with the persistent labelling of journalists as unpatriotic; “… the South African Native found himself, not actually a slave, but a pariah in the land of his birth.”

Our journalists today find themselves, not actual slaves of authoritarianism, but pariahs to governments’ in their pursuit of truth, justice and democratic values. We need a rebirth of the principles and spirit of Sol Plaatje now more than ever.

Join the Conversation